Database Vacuum Explained

Prefer Video?

TL;DR;

Vacuum is an operation that reclaims storage occupied by dead tuples (garbage-collect and optionally analyze a database)

Deep Dive

Why should I care about it?

I don’t care if you care about it or not. However, if you want to know what really happens when you are doing DELETE or UPDATE, then you should check this explanation.

In order to explain what VACUUM is we need to understand some basics such as row / column oriented storage and database page layout.

What Is a TUPLE?

In the context of a database, a tuple is simply a single row in a table. It represents a single, structured data item in a collection of items.

Each tuple is an ordered set of values, where each value corresponds to a specific column or attribute of the table.

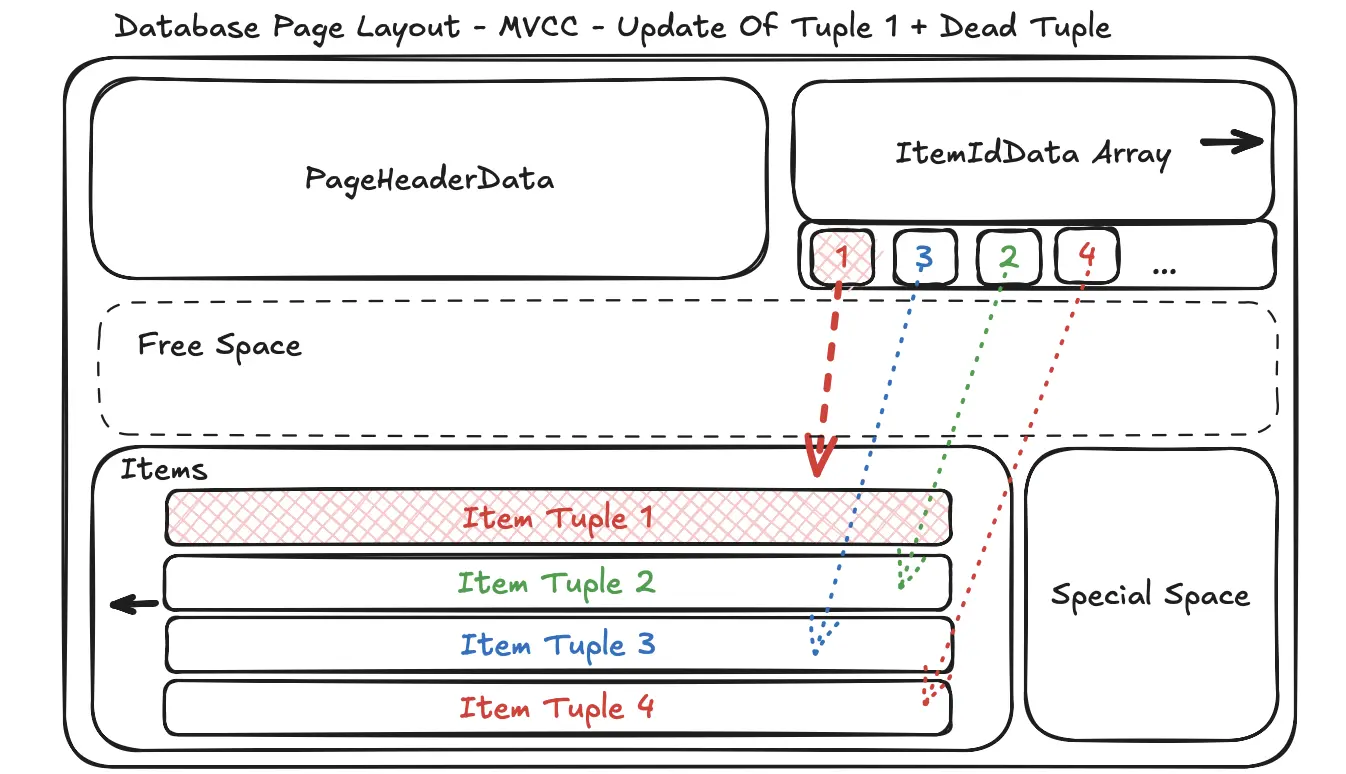

Data is stored in fixed-size blocks called pages (e.g., 8KB or 16KB). A common and efficient way to organize tuples within a page is the Slotted Page Layout.

- Page Header: Contains metadata about the page, such as how much free space is left, the page number, and how many tuples it contains.

- Tuple Data: The actual data for each tuple is stored on the page. To save space, new tuples are typically added from the end of the page, growing backward.

- Slot Array (or Item Pointer Array): This is an array of pointers that sits right after the header. Each pointer in this array “points” to the exact location of a single tuple within the page.

More about page layout in my previous post HERE.

When you query a database, it reads the required pages from the disk into a memory area called the buffer pool.

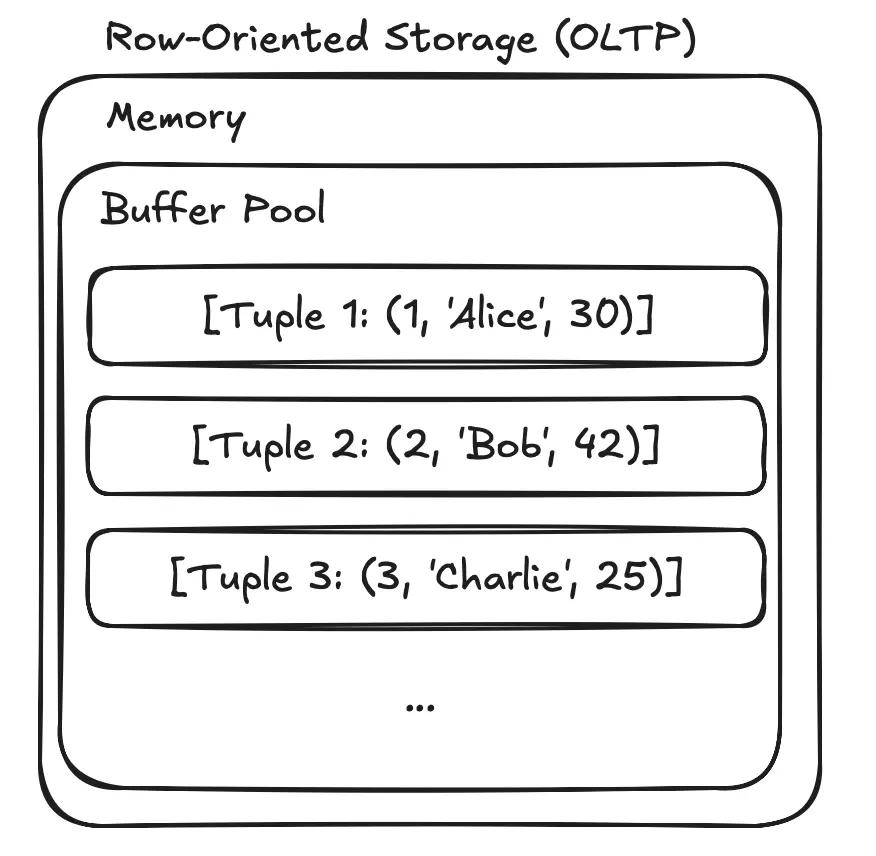

Row-Oriented Storage (OLTP)

For most traditional databases (like MySQL, PostgreSQL, SQL Server), the in-memory structure mirrors the on-disk page structure. The tuple is kept as a contiguous block of bytes. This is excellent for transactional workloads (Online Transaction Processing or OLTP) where you frequently need to access, insert, or update an entire row at once (e.g., retrieving all information for a specific user).

Example: Tuples are laid out one after another. [Tuple 1: (1, 'Alice', 30)] [Tuple 2: (2, 'Bob', 42)] [Tuple 3: (3, 'Charlie', 25)]

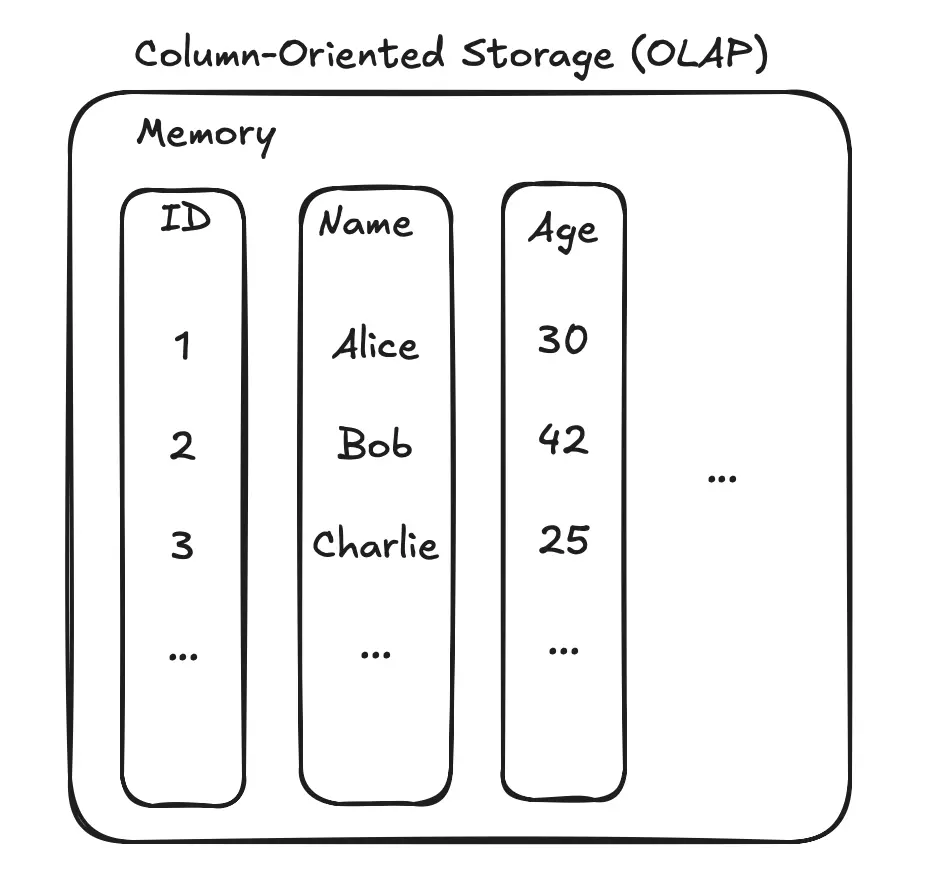

Column-Oriented Storage (OLAP)

For analytical databases (like Google BigQuery, Amazon Redshift, Snowflake), data is often organized by columns, not rows. All values for the ID column are stored together, all values for the Name column are stored together, and so on.

This is extremely efficient for analytical queries (Online Analytical Processing or OLAP) that aggregate data from a few columns across millions of rows (e.g., SELECT AVG(Age)). The database only needs to read the Age column data, ignoring the ID and Name columns completely, which saves a massive amount of I/O and processing time.

Example:

- ID Column Store:

[1, 2, 3, ...] - Name Column Store:

['Alice', 'Bob', 'Charlie', ...] - Age Column Store:

[30, 42, 25, ...]

DEAD TUPLE

A dead tuple is a version of a row that has been made obsolete by a DELETE or UPDATE operation but hasn’t been physically removed from the data page yet.

The main reason for keeping dead tuples around temporarily is a concept called Multiversion Concurrency Control (MVCC).

The core idea: readers should not block writers, and writers should not block readers.

Example

- 10:05:40 AM: Your long-running analytics query starts. It begins scanning the

userstable. - 10:05:41 AM: While your query is running, another process executes

UPDATEoperation for AliceUPDATE users SET age = 33 WHERE id = 1;

Without MVCC, the database would have to “lock” the row, and your query would either fail or have to wait.

With MVCC, the database does something smarter:

- It doesn’t overwrite the original tuple

(1, 'Alice', 30). - Instead, it marks the original tuple as “dead” (or more accurately, it sets a “max transaction ID” on it, meaning it’s invisible to any transaction starting after this point).

- It then creates a new tuple

(4, 'Alice', 33)which is the “live” version.

Your long-running query, which started before the update, is still allowed to see the old, consistent version of the data (1, 'Alice', 30). Any new query starting after the update will see the new, live tuple (4, 'Alice', 33).

This creates multiple “versions” of the data, hence the name Multiversion Concurrency Control.

Obviously, these dead tuples can’t just pile up forever. They take up valuable disk space and can slow down table scans because the database has to read them and then check if they are visible to the current transaction.

This is where a process called vacuuming (or garbage collection) comes in.

And here my Dear Fellow we are reaching VACUUM.

A background process, often called VACUUM, periodically scans tables for dead tuples. It determines which dead tuples are no longer visible to any running transaction.

Once a tuple is confirmed to be “truly dead,” the VACUUM process marks the space it occupies as free and available for new rows to be inserted.

VACUUM Key Points

- PostgreSQL Documentation

- At least

MAINTAINprivilege on the table - Cannot be executed inside a transaction block

PARALLELoption affectsVACUUMnotANALYZEpart- VACUUM causes a substantial increase in I/O traffic, which might cause poor performance for other active sessions

- VACCUM statement is not part of SQL standard

VACUUM Most Notable Execution Options

- FULL - reclaim more space, but takes much longer and exclusively locks the table. This method also requires extra disk space, since it writes a new copy of the table and doesn’t release the old copy until the operation is complete. Usually this should only be used when a significant amount of space needs to be reclaimed from within the table.

- VERBOSE - Prints a detailed vacuum activity report for each table.

- ANALYZE - Updates statistics used by the planner to determine the most efficient way to execute a query.

- PARALLEL - Perform index vacuum and index cleanup phases of

VACUUMin parallel usingintegerbackground workers. The number of workers used to perform the operation is equal to the number of indexes on the relation that support parallel vacuum which is limited by the number of workers specified withPARALLELoption if any which is further limited by max_parallel_maintenance_workers Please note that it is not guaranteed that the number of parallel workers specified inintegerwill be used during execution. It is possible for a vacuum to run with fewer workers than specified, or even with no workers at all. Only one worker can be used per index. So parallel workers are launched only when there are at least2indexes in the table.

What is cost-based vacuum delay feature? For parallel vacuum, each worker sleeps in proportion to the work done by that worker.

- INDEX_CLEANUP - Normally,

VACUUMwill skip index vacuuming when there are very few dead tuples in the table. The cost of processing all of the table’s indexes is expected to greatly exceed the benefit of removing dead index tuples when this happens. This option can be used to forceVACUUMto process indexes when there are more than zero dead tuples. The default isAUTO, which allowsVACUUMto skip index vacuuming when appropriate. IfINDEX_CLEANUPis set toON,VACUUMwill conservatively remove all dead tuples from indexes. This option has no effect for tables that have no index and is ignored if theFULLoption is used. It also has no effect on the transaction ID wraparound failsafe mechanism.

What is transaction ID wraparound failsafe mechanism?

The transaction ID wraparound failsafe mechanism is an emergency procedure that PostgreSQL triggers to prevent the database from having to shut down. This procedure aggressively cleans up old row versions to stop its internal transaction counter from resetting incorrectly.

The Problem: A Clock That Runs Out of Numbers

PostgreSQL’s concurrency model (MVCC) works by assigning a unique Transaction ID (TXID) to every transaction that modifies data (INSERT, UPDATE, DELETE). This TXID is just a 32-bit integer, meaning it has a finite range of about 4 billion unique numbers.

Once the counter reaches its maximum value, it must wrap around and start back at a low number.

This creates a paradox. PostgreSQL decides if a row is visible to your query by comparing the row’s TXID to your current transaction’s TXID. A row is “in the past” and visible if its TXID is lower than yours. But after a wraparound, a very old TXID (e.g., 3.5 billion) can suddenly appear to be “in the future” compared to a new TXID (e.g., 100).

If this happens, the database can no longer tell which rows are old and which are new. It would start hiding valid, committed data, effectively causing massive data corruption.

To prevent this data corruption, PostgreSQL has a hard rule: **it will shut down and refuse to accept any new write commands before the wraparound can occur.

The Solution: VACUUM and “Freezing”

The primary defense against this shutdown is the VACUUM process. One of VACUUM’s most important jobs is to perform “freezing.”

When VACUUM runs, it scans the tables and finds very old rows whose TXIDs are no longer needed for concurrency checks.It then “freezes” these rows by replacing their old TXID with a special, permanent value (FrozenTransactionId) that is always considered to be in the past. This frees up the old TXIDs to be reused safely after the counter wraps around.

The regular autovacuum process handles this freezing routinely in the background.

The “Failsafe Mechanism”

The failsafe mechanism is an emergency autovacuum that kicks in when the database gets dangerously close to wraparound (e.g., it has used up over 1.6 billion transaction IDs, as defined by the vacuum_failsafe_age setting).

This isn’t a normal vacuum. It takes extraordinary measures to finish as quickly as possible:

- It ignores cost-based delays, meaning it consumes as much I/O and CPU as it needs to get the job done fast.

- It skips non-essential tasks, like index vacuuming, to focus purely on the critical task of freezing rows and advancing the table’s “oldest TXID” horizon

That’s All Folks …

So, VACUUM is much more than a simple janitor for your database. We’ve seen that the concept of “dead tuples” isn’t a flaw, but a fundamental part of how PostgreSQL’s MVCC allows for high concurrency without locking. However, these obsolete rows must be cleaned up, and that’s where VACUUM begins its work.

It’s a process with a dual mandate. On one hand, it performs the routine, but crucial, task of reclaiming disk space and updating statistics with ANALYZE to keep queries running efficiently. On the other, it serves as the indispensable guardian against the catastrophic transaction ID wraparound problem. By “freezing” old rows, VACUUM ensures the database can run continuously for decades without risking data corruption or a forced shutdown.

The next time you hear about database maintenance, you’ll know that VACUUM isn’t just about tidying up it’s a core part of what makes a database like PostgreSQL so robust, reliable, and performant.

Thanks,

Krzysztof

Want to be up to date with new posts?

Use below form to join Data Craze Weekly Newsletter!