Database Page Layout Explained

Prefer Video?

How exactly your tables and rows from your relational databases (in case of this example - PostgreSQL specifically) translates into saved data on storage?

To answer this question properly we would need to introduce a database page layout, but before that let’s start with some PostgreSQL specifics.

PGDATA

For PostgreSQL database this is the place where configuration and data files used by a database cluster are stored together.

A common location for PGDATA is /var/lib/pgsql/data.

Multiple clusters, managed by different server instances, can exist on the same machine.

What is included in PGDATA is described in details in documentation - HERE

In addition, this is the place where cluster configuration files are stored (but they can be moved elsewhere): - postgresql.conf - pg_hba.conf - pg_ident.conf

For each database in the cluster there is a subdirectory within PGDATA/base, named after the database’s OID in pg_database.

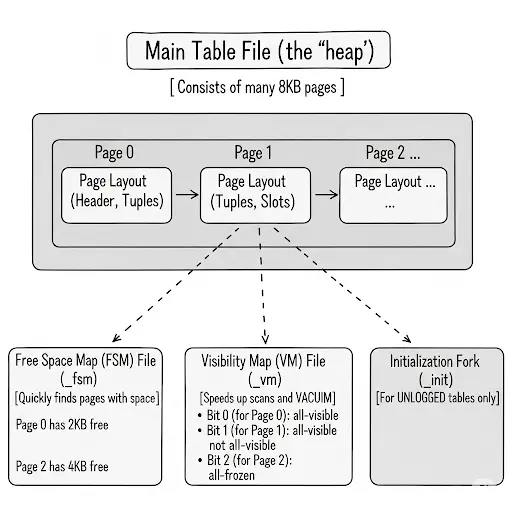

Main Table File (‘heap’)

Database Page

Every table and index is stored as an array of pages of a fixed size (usually 8 kB, although a different page size can be selected when compiling the server). In a table, all the pages are logically equivalent, so a particular item (row) can be stored in any page. In indexes, the first page is generally reserved as a metapage holding control information, and there can be different types of pages within the index, depending on the index access method.

n the following explanation, a byte is assumed to contain 8 bits. In addition, the term item refers to an individual data value that is stored on a page. In a table, an item is a row; in an index, an item is an index entry.

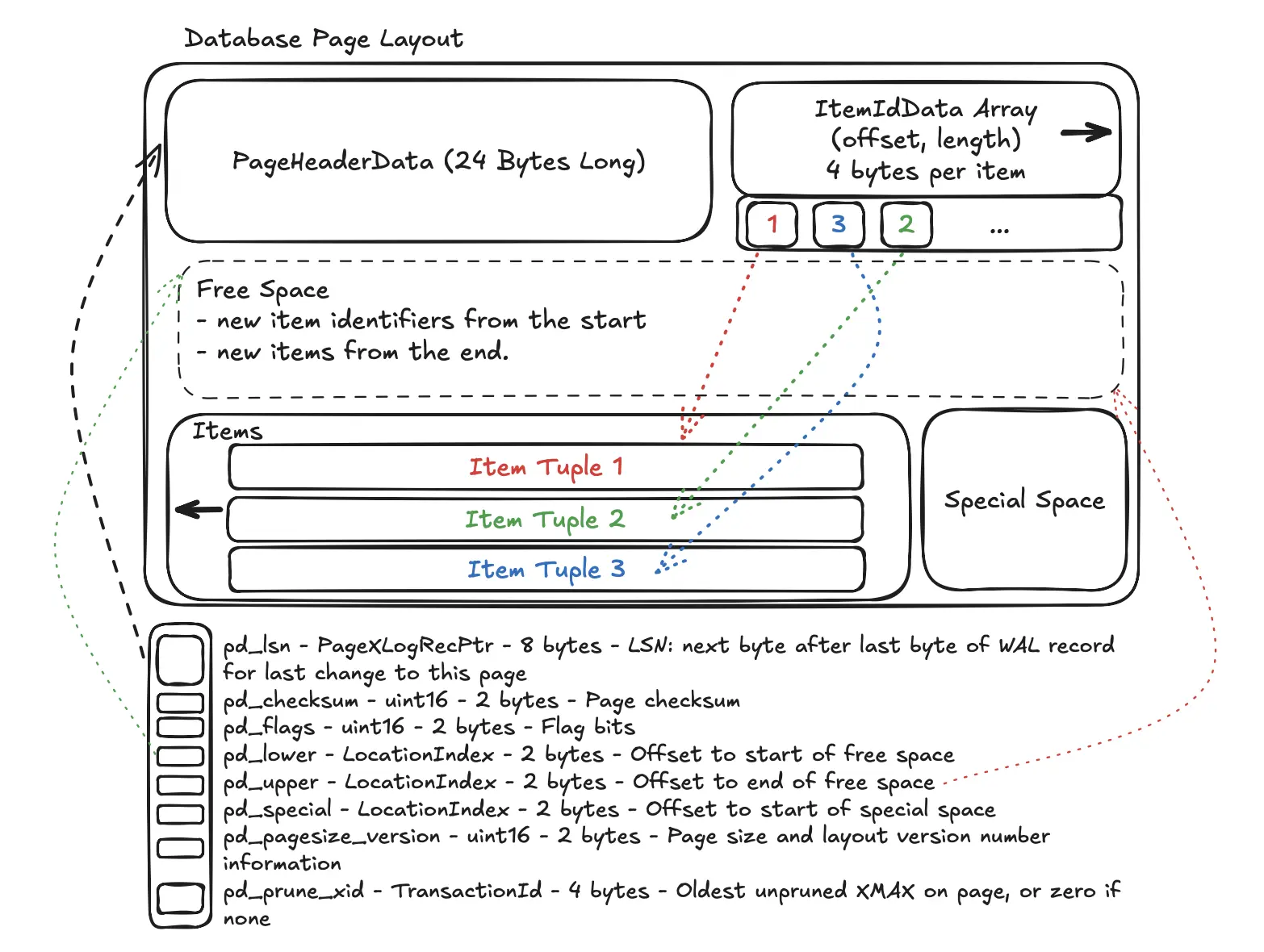

Page Layout

- PageHeaderData: 24 bytes long. Contains general information about the page, including free space pointers.

- pd_lsn - PageXLogRecPtr - 8 bytes - LSN: next byte after last byte of WAL record for last change to this page

- pd_checksum - uint16 - 2 bytes - Page checksum

- pd_flags - uint16 - 2 bytes - Flag bits

- pd_lower - LocationIndex - 2 bytes - Offset to start of free space

- pd_upper - LocationIndex - 2 bytes - Offset to end of free space

- pd_special - LocationIndex - 2 bytes - Offset to start of special space

- pd_pagesize_version - uint16 - 2 bytes - Page size and layout version number information

- pd_prune_xid - TransactionId - 4 bytes - Oldest unpruned XMAX on page, or zero if none

- ItemIdData: Array of item identifiers pointing to the actual items. Each entry is an (offset,length) pair. 4 bytes per item.

- CTID - is as ItemPointer to an item in page created by PostgreSQL consists of a page number and the index of an item identifier.

- Free space: The unallocated space. New item identifiers are allocated from the start of this area, new items from the end. It shrinks from both sides as new

ItemIdpointers and newItemsare added. - Items: The actual row data (tuples) are stored here. New items are added from the end of the page and grow backwards (from right to left). The

pd_upperpointer in the header marks the start of the most recently added item.- All table rows are structured in the same way.

- t_xmin - TransactionId - 4 bytes - insert XID stamp

- t_xmax - TransactionId - 4 bytes - delete XID stamp

- t_cid - CommandId - 4 bytes - insert and/or delete CID stamp (overlays with t_xvac)

- t_xvac - TransactionId - 4 bytes - XID for VACUUM operation moving a row version

- t_ctid - ItemPointerData - 6 bytes - current TID of this or newer row version

- t_infomask2 - uint16 - 2 bytes - number of attributes, plus various flag bits

- t_infomask - uint16 - 2 bytes - various flag bits

- t_hoff - uint8 - 1 byte - offset to user data

- All table rows are structured in the same way.

- Special space: Index access method specific data. Different methods store different data. Empty in ordinary tables.

Free Space Map (FSM)

Purpose

To quickly find a page with enough free space to fit a new row (or an updated row that grew in size).

How it Works

Instead of scanning the main table file page-by-page to look for space (which would be very slow for large tables), PostgreSQL consults the FSM. The FSM is a compact data structure that tracks the amount of free space on each page. When you run an INSERT, the database asks the FSM, “Hey, where’s a page with at least N bytes free?”

Analogy

It’s like a parking garage display that tells you how many empty spots are on each level, so you don’t have to drive up and down every single aisle to find one.

Visibility Map (VM)

Purpose

To dramatically speed up certain types of queries and VACUUM operations.

How it Works

The visibility map stores two bits per heap page, where each bit corresponds to a page in the main table file.It tracks two key pieces of information per page:

- All-Visible:

- If this bit is set, it means every single row on that page is visible to all current and future transactions.

- This allows for index-only scans.

- If a query can be satisfied just by looking at an index, the VM confirms that a trip to the main table file to check row visibility isn’t needed, saving a huge amount of I/O.

- All-Frozen:

- If this bit is set, it tells

VACUUMthat all rows on this page have already been “frozen” and are safe from transaction ID wraparound. VACUUMcan then skip scanning this page entirely, making its job much faster.

- If this bit is set, it tells

Initialization Fork

Purpose

This is a special file used only for UNLOGGED tables.

How it Works

UNLOGGED tables are fast because their changes aren’t written to the Write-Ahead Log (WAL), but this also means they are not crash-safe. If the database server crashes, an UNLOGGED table is automatically truncated. The _init fork is what makes this possible. On a crash recovery, PostgreSQL simply copies the (usually empty) _init fork over the main table file, effectively wiping it clean. For a regular, durable table, this fork doesn’t play a role.

TOAST

TOAST - The Oversized-Attribute Storage Technique)

PostgreSQL uses a fixed page size (commonly 8 kB), and does not allow tuples to span multiple pages. Therefore, it is not possible to store very large field values directly. To overcome this limitation, large field values are compressed and/or broken up into multiple physical rows. This happens transparently to the user, with only small impact on most of the backend code. The technique is affectionately known as TOAST. The TOAST infrastructure is also used to improve handling of large data values in-memory.

Only certain data types support TOAST — there is no need to impose the overhead on data types that cannot produce large field values. To support TOAST, a data type must have a variable-length (varlena) representation, in which, ordinarily, the first four-byte word of any stored value contains the total length of the value in bytes (including itself).

Out-of-Line, On-Disk Toast Storage

Out-of-line values are divided (after compression if used) into chunks of at most TOAST_MAX_CHUNK_SIZE bytes (by default this value is chosen so that four chunk rows will fit on a page, making it about 2000 bytes). Each chunk is stored as a separate row in the TOAST table belonging to the owning table. Every TOAST table has the columns chunk_id (an OID identifying the particular TOASTed value), chunk_seq (a sequence number for the chunk within its value), and chunk_data (the actual data of the chunk). A unique index on chunk_id and chunk_seq provides fast retrieval of the values.

Out-of-line, In-Memory TOAST Storage

TOAST pointers can point to data that is not on disk, but is elsewhere in the memory of the current server process. Such pointers obviously cannot be long-lived, but they are nonetheless useful. There are currently two sub-cases: pointers to indirect data and pointers to expanded data.

That’s All Folks …

And there you have it! We’ve journeyed from the high-level PGDATA directory, which acts as the home for a PostgreSQL cluster, all the way down to the byte-level structure of a single database page.

We’ve seen that a table is not just one big file, but a collection of 8KB pages, each with a meticulously organized layout of headers, item pointers, and the row data itself. We’ve also uncovered the crucial roles of the Free Space Map (FSM) and Visibility Map (VM), the unsung heroes that make data retrieval and maintenance operations fast and efficient. Finally, we explored how PostgreSQL cleverly handles large data with its TOAST mechanism, keeping the main table lean.

Understanding this storage architecture reveals the incredible engineering that allows a relational database to perform complex tasks with impressive speed and reliability. The next time you run a simple SELECT query, you’ll have a much deeper appreciation for the intricate dance of pages, pointers, and maps happening under the hood.

Thanks,

Krzysztof

Want to be up to date with new posts?

Use below form to join Data Craze Weekly Newsletter!